Exactly ten years ago, at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate and Climate Change (COP21), scientists and politicians from 195 countries gathered in Paris to create a plan to prevent climate catastrophes and ensure a sustainable future. The Paris Agreement, hailed as “the greatest success of international diplomacy” and “a major step forward for humanity”, was not a comprehensive plan, but rather an almost universal commitment that was expected to be followed by further, science-based steps toward faster and substantial climate action.

Many hoped, and believed, at the time that this would mark the beginning of a new era for global politics, characterized by stronger international cooperation, mutual commitments, and solidarity, also guided by the 17 ambitious UN Sustainable Development Goals. Indeed, the then UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, often stated that the struggle for sustainable development would define the 21st century, just as the fight for human rights defined the 20th.

Today, however, especially after the geopolitical upheavals of recent years, the situation is very different. The most visible shift has been the change in the stance of the United States under Donald Trump, a staunch climate change denier. President Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement (first in 2017 and again in 2025), repealed his predecessor’s Inflation Reduction Act -which, despite its distortions to the global economy, aimed to support a new green economy- consistently dismisses climate science, and expanded fossil fuel extraction, including coal. It is worth noting that, while in 2015 the U.S. was a negligible player in the natural gas market and American oil exports were still banned, today it is the world’s largest exporter of both oil and liquefied natural gas.

The changes are not limited to the United States. The first act of Mark Carney, a Canadian economist who had contributed to the Paris Agreement, upon assuming the premiership of his country, was to abolish the carbon tax. The President of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, a climate scientist and academic, now speaks of “energy sovereignty” and has increased oil and gas extraction, enjoys broad popular support. In Europe, too, there is an increase of voices -including that of Greece- that call for the weakening of environmental legislation and a slowdown of the green transition, and diverge from the common line, as seen the recent vote on zero carbon in shipping at the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The rollback of climate policies is evident everywhere, and more politicians now talk not about “climate action” but about “climate realism” as the pressing need. Notably, while between 2019 and 2021 more than 300 new mitigation and adaptation policies were adopted globally, in 2023 that number dropped below 200, and in 2024 there were only 50!

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report 2024 highlighted that no progress had been made toward global climate targets -in fact, emissions had increased by 1.2%. It also noted that under current targets, emissions would fall by only 5.9% by 2030, instead of the 43% needed to stay on the path 1.5°C. Meanwhile, dozens of the original architects of the Paris Agreement have sent an open letter to the UNFCCC, calling for a review of the “outdated” COP mechanism, which they said can no longer guarantee “timely and effective action at the scale required to secure humanity’s climate future”.

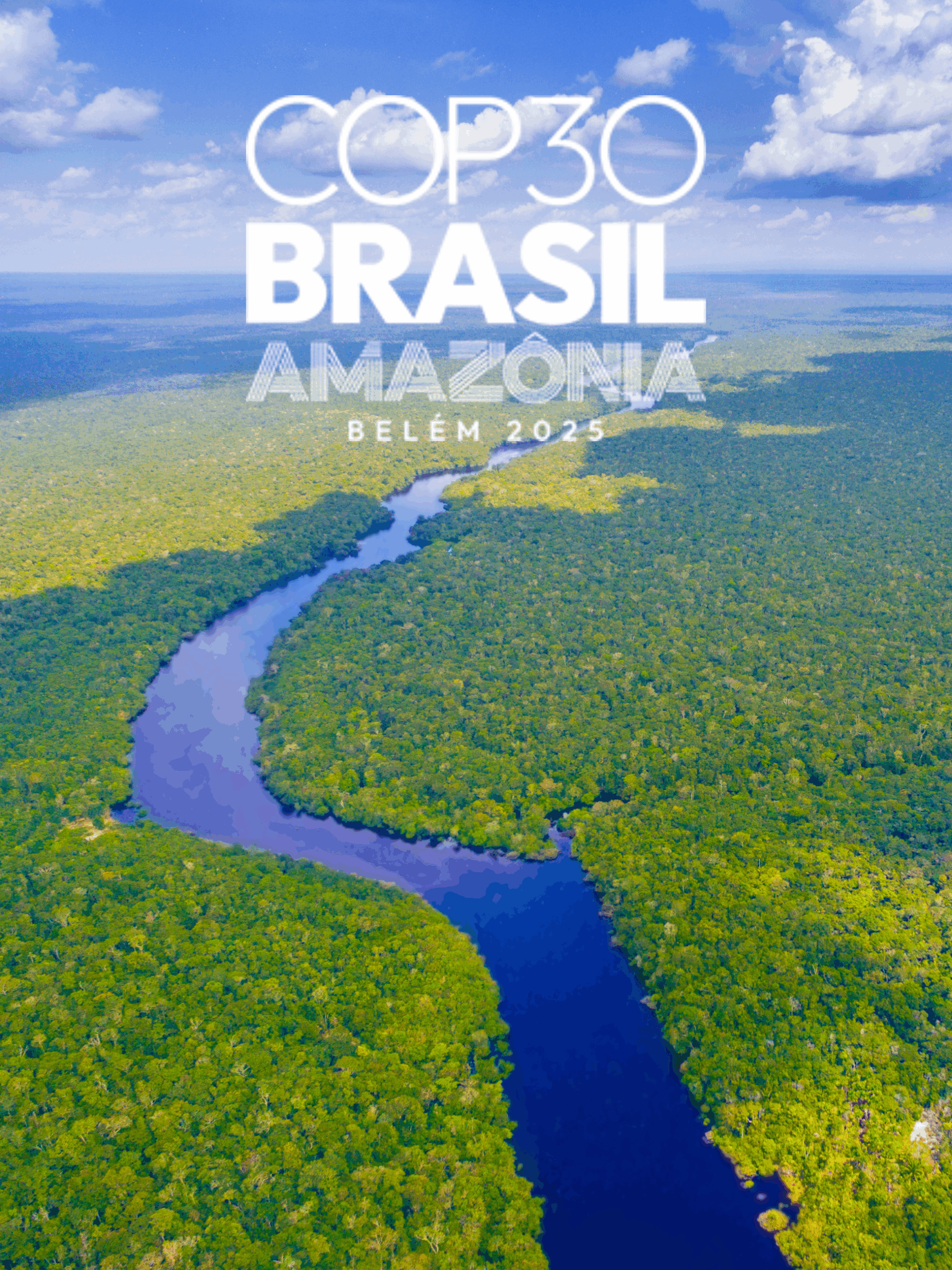

Against this backdrop, COP30 opens today in a symbolic location, the town of Belém, in Brazil, the main gateway to the Amazon. Brazil’s Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, Marina Silva, had described it last year at the Baku conference as “the mother of all COPs”.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has already convened a meeting of world leaders, ahead of the official opening, though the “big” leaders of the U.S., China, India, and Russia are notably absent. President Lula da Silva emphasized that the era of speeches and good intentions is over, declaring that “… COPs can no longer be meetings of negotiations and fine ideas. They must become moments of truth and real action to confront the climate crisis … 2025 must be the year we channel all our grief [for climate disasters], all our indignation, into constructive, collective action!”. He also did not fail to criticize the “… extremist voices that manufacture fake news, condemning future generations to live on a planet ravaged by climate change,” an implicit reference to the U.S. President.

Let us now look at the main issues at stake in this year’s conference, areas where meaningful decisions are needed to begin closing the gap between words and action.

Revision of National Climate Targets (NDCs). According to the Paris Agreement, countries were expected to submit updated Nationally Determined Contributions by February. When the deadline passed, only 15 countries (8%) had complied. By mid-October the number had risen to 86, but very few of the new targets are aligned with the 1.5°C pathway (among them, those of the U.K. and Brazil), and many show regression. The plans of major players -the EU, U.K., China, and India- will be decisive, as many smaller countries are waiting to see their commitments before submitting their own.

Financing for Developing Countries. Ambitious plans are meaningless without the necessary resources. At Baku, developed countries agreed to mobilize at least $300 billion annually, though real needs are estimated at over $1.3–4 trillion per year. Recently, the COP30 Presidency published the Baku to Belém Roadmap, a framework with five pillars aimed at engaging all stakeholders, from governments to the private sector, to increase climate finance to $1.3 trillion by “expanding supply, targeting demand, and enhancing access and transparency”. The document is non-negotiable and imposes no binding commitments, instead emphasizing substantive dialogue among all parties. In this context, it is important to remember that the U.S. has drastically cut international economic aid programs, while other countries such as France, Germany, and the U.K. have also announced reductions.

Adaptation. The implementation areas of the Global Goal on Adaptation -water, health, ecosystems, infrastructure, poverty eradication, and cultural heritage- were agreed upon at COP28. However, the indicators for progress monitoring and evaluation were deferred to this year’s COP. The adaptation finance gap is estimated at $187–359 billion annually, with severe impacts on the most vulnerable countries and communities amid escalating climate disasters. Many organizations and governments are pushing for a new, specific funding target, as the previous one -doubling adaptation finance, agreed in Glasgow (COP26)- expires this year. Meanwhile, the COP30 Presidency urges countries to prepare and submit National Adaptation Plans.

Nature as Climate Infrastructure. A key pillar will be reversing deforestation and restoring ecosystems. Brazil is set to announce a new, innovative mechanism, the Tropical Forest Recovery Facility, which will function as an investment vehicle rather than a donation fund, rewarding those who preserve forests. President Lula da Silva has pledged $1 billion to the scheme. In an unexpected reversal, the U.K. government announced last Wednesday that it is withdrawing its promised $125 billion contribution, a move that has angered Brazil’s government.

Phasing Out Fossil Fuels. Despite its cautious language and many loopholes for the oil industry, the final text of COP28 emphasized the need for a “transition away from fossil fuels,” setting goals such as tripling global renewable energy capacity and doubling energy efficiency improvement rates by 2030; accelerating efforts to phase out unabated coal power; transitioning from fossil fuels in a “just, orderly, and equitable” manner to achieve net zero by 2050; and eliminating, as soon as possible, inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or a just transition. Although renewables now provide more than 50% of global electricity demand, progress on the other targets has been slow, hindered both by the fossil fuel industry and by President Trump’s aggressive efforts to commit as many countries as he can to US LNG, and weaken their climate targets by blackmailing with trade wars and tariffs.

The COP30 Presidency, since June, has presented the Climate Action Agenda, reaffirming its commitment to the 2023 Global Stocktake agreement and promising that this year’s conference will deliver a plan for a “coordinated and just phaseout of fossil fuels”. It has also called for a global “mutirão”,[1] a “people’s collective effort for the progress of humanity”.

Progress, though essential, remains uncertain and will depend on the Brazilian Presidency’s capacity to resist pressure and transform vague promises into firm commitments and tangible action.

While we await the outcome, let us keep in mind the words of Ana Toni, CEO of COP30, who said: “The COP is only one moment in the year. What truly matters is what governments, businesses, and citizens do all the rest of the time”.

[1] The term mutirão originates from the indigenous peoples of Brazil and is used to describe how members of a community work together towards a common goal, or to support each other.